by Jakob Schoof, Editor of Daylight & Architecture

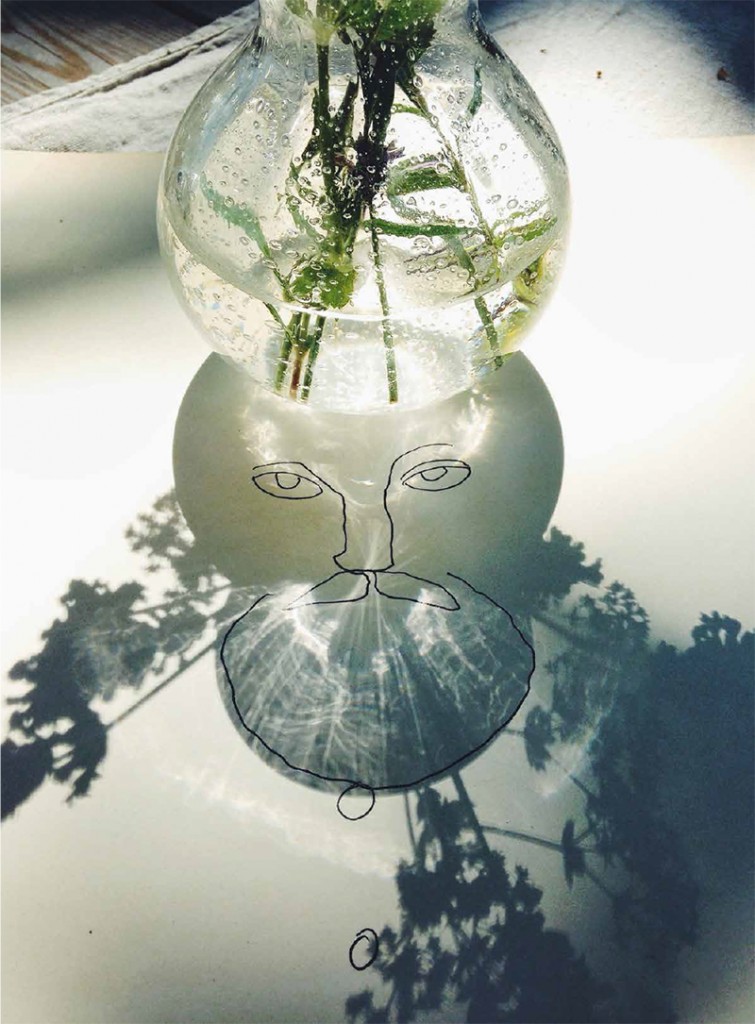

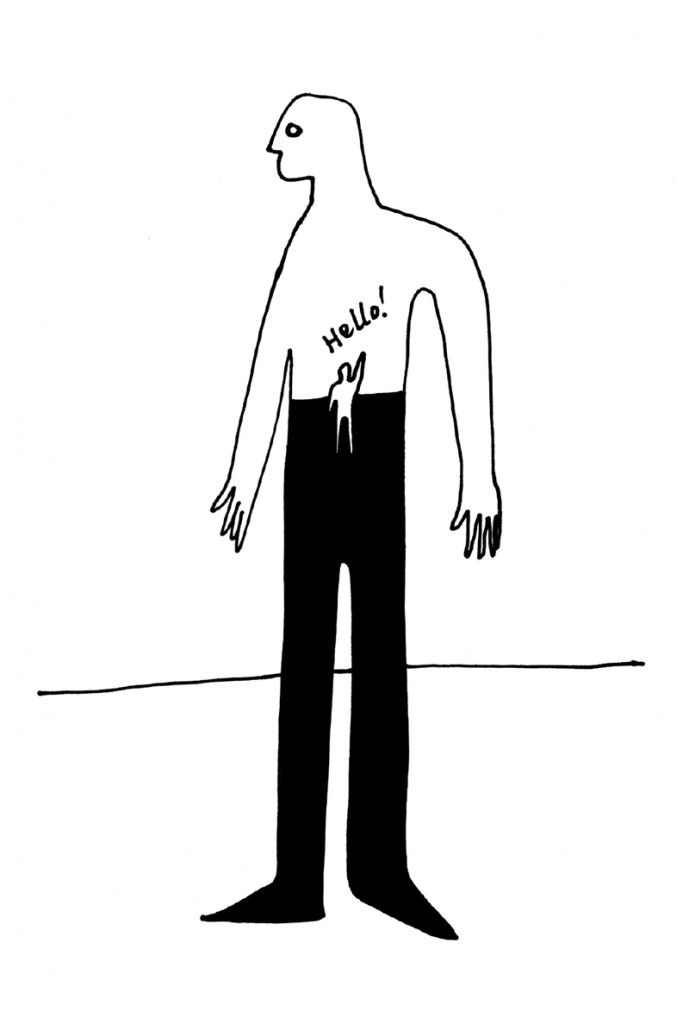

In surveys and polls, climate protection and preservation of the environment are repeatedly referred to as important issues. But the successes achieved up to now are relatively modest. This will not change until people arrive at the insight that it is ourselves that are the main concern, not kilowatt hours and tons of carbon. Nature is not something that needs protection far removed from civilisation; it is the basis of all our lives, right here and now. It must therefore be rendered visible and noticeable in our cities again. This not only applies to flora and fauna but also to more intangible natural phenomena such as the air that we breathe, the light that we let into our homes and even the rhythms of nature that still affect us in the 24-hour society.

What is nature worth to us? Until ten years ago, it would only have been possible to answer this question in a philosophical sense. Since then, however, hundreds of economists, biologists, geographers and climate researchers have been trying to express the answer in more concrete form. In the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment of the United Nations, 1 published in 2005, they undertook the first attempt to systematically make a record of all the resources and services that nature provides us with. Under the heading Ecosystems and Human Well- Being, the report provided a compelling account of how much we depend on nature – materially and for our health as well as culturally and spiritually.

In the public discussion of the report, there was a lot of talk about nature as the supplier of food, raw materials and medically effective substances. In contrast, there was hardly any discussion of nature’s less tangible services – in other words, of how important urban parks are for people‘s physical and mental wellbeing, of how much we need clean air to breathe and daylight to regulate our circadian rhythm.

All of this highlights people’s understanding of nature today. On the one hand, stressed-out city dwellers instinctively know the value of direct contact with nature. Any real-estate listing demonstrates this; houses in garden cities or directly next to parks and green spaces command the very highest prices, as do city penthouses offering maximum daylight, spectacular views and large allround roof terraces.

On the other hand, these priorities are often forgotten when people decide about issues that do not directly affect their personal living environment. In such cases, urban density or low energy consumption are often paraded as objectives to which everything else supposedly has to be subordinated – in cases of doubt, even the well-being of the inhabitants. Abstract mathematical variables frequently replace good judgement and healthy common sense.

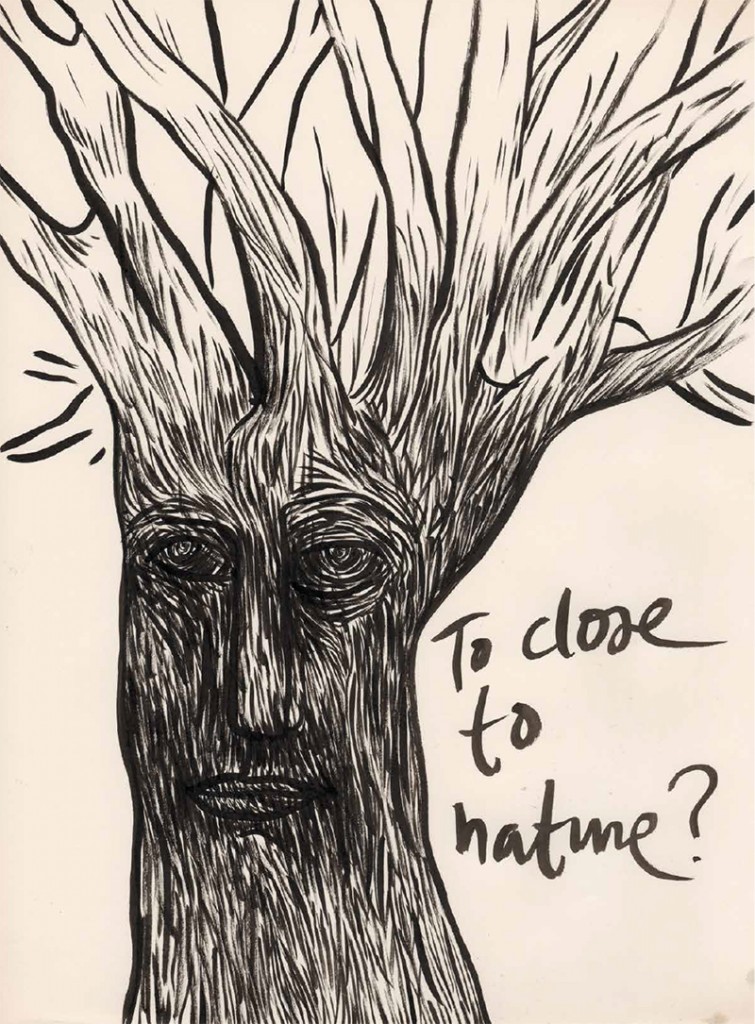

This ignorance ought to be overcome. We don’t just need nature as a supplier of food, raw materials and other resources that can be assigned a price. Nor is nature a self-enclosed entity outside our civilisation that we ought to protect for its own sake; it is the basis of our existence in a very direct way – particularly in the world’s cities, which will soon accommodate three quarters of the global population. If we really want to preserve nature – and therefore our entire civilisation, which is, after, all dependent on it – we have to make it visible in everyday life. In his book The Nature Principle, the journalist Richard Louv writes, “We cannot protect something we do not love, we cannot love what we do not know, and we cannot know what we do not see. Or hear. Or sense.”

|

|

|

For more information about Daylight & Architecture visit DA.VELUX.com.